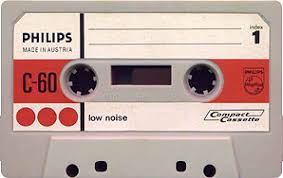

In part 2, I wrote about how recording sound on tape in the ‘50s-‘60s had taken over from recording direct to metal discs and its’ resulting popularity in the domestic market. The next technology move on was the Compact Cassette.

RCA in the ‘States recognised that lumbering big tape recorders and reels of tape around was not the most convenient of pastimes. They came up with a cased set of two small reels of tape, calling it a cassette. It was about 5” by 7”, still too big and commercially flopped. In ’63, Philips had developed and released the Compact cassette as we know it. It was shown at the Berlin Radio show and released into Europe in ’64. A massive hit. The Compact Cassette consisted of a plastic case, 4” x “.5”, containing 2 reels of 1/8th” wide tape. The cassette had two holes which fitted onto the players’ hubs for take up and winding back and forth and the tape was exposed at the front so that the recording / playback head and capstan and pinch roller could make contact with the tape.

The tapes width was half that of the standard “open reel” type and so was the speed that the tape travelled (1&7/8th inches a second). Although the design was subject to patents, Philips agreed to allow Sony to manufacture, which lead to Japan dominating the market. Philips released a great little Cassette machine in ’64 called the Carry-Corder, type EL3302. It was an iconic design, simple to use with one control. Up for play and left and right for wind forward and back. A copy of the BSR tape decks popular in ‘50s.

Because the tape was narrow and moved slowly across the recording and playback head of the machine, audio quality, bandwidth and signal to noise was not great. It was ok to record Uncle Jack down the boozer on a Saturday night. Initially, the tapes magnetic composition was made of ferric oxide, fine rust is you like. Light brown in appearance and not too durable. Toward the late ‘60s companies such as TDK, 3M etc were coming up with new coatings made from Cobolt and Chromium Dioxide. These gave a much better recording quality and lower background noise. Dolby Labs had designed a system whereby the audio signal was processed, minimizing the annoying hiss which could be heard during quiet passages. The cassettes quality now matched that of the LP record.

Because there were several types of tape composition, machines had to be adjusted to get the best out of the tape. Changes in “Bias” (method by which the sound was recorded onto the tape) had to be made for standard, Chrome etc… Earlier machines had switches so you could play around with on the front panel, some machines made use of the little cut-outs in the rear of the cassette. Here the manufacturers made holes in the cassette housing which when placed in the cassette deck, married up with little switches, automatically setting the correct conditions. You also had different types of Dolby to switch, A, B, C and latterly D.

A big boost in sales came with Sony’s release of the Walkman. This was a personal cassette player aimed at people who indulged in that stupid pastime of jogging. All sounded great until you stared to jog however. The movement upset the rotation on the little capstan flywheel whose purpose was to move the tape at constant speed and music wobbled all over the place. Later machines had two flywheels working in opposition, so the effects of your jogging cancelled out.

Companies such as Nakamici, Revox made some excellent semi professional machines that managed to squeeze every last drop of quality out of the cassette. Sony & Teac developed a variation called the Elcaset. This was a much larger cassette with ¼” tape with a speed of 3&3/4” inches a second. Quality was great and with the use of Dolby, these could compete against big reel to reel machines. In fact they were often used as data storage machines to record early facsimile transmissions. However, with the introduction of CDs in early ‘80s, the cassettes’ days were numbered. So we say good bye to the C30, C90 and C120 and messing about with winding the spilled tape back in with a pencil or Biro!