Abbey Road Recording Studios

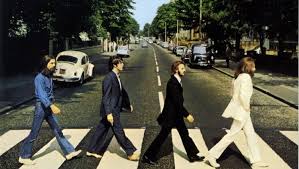

We have all seen the famous photo of the Beatles walking across the zebra crossing toward Abbey Road Studios. Where did that all begin I hear you frantically ask.

In the 1920s, entertainment mainly revolved around the new BBC radio and records. “The Gramophone” company was responsible for producing the lion´s share of records in Britain. The company had a couple of studios in the West End of London and Hayes in Middlesex. The Gramophone Company merged with it’s competitor Columbia and in the early ´30s, the newly named merger, Electric Musical Industries (EMI) decided to look for a site where a cutting edge set of studios could be built. Plots 3 and 5 In St John´s Wood, London were acquired and a 3 studio establishment was built, opening in 1931. Celebration recording was made of the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir Eddy Elgar himself.

Studio 1 was big enough to house a 100 piece orchestra. With a 28 foot ceiling and clever acoustics, the results were fantastic. Studio 2, over the next 30 years saw recordings made of all the big bands, comedy acts such as Peter Sellers, Bernard Cribbins the Goons to name but a few. In June 1962, 4 guys from Liverpool walked into Abbey Road Studios to make a test recording with producer George Martin. They had previously been turned down by recording giant Decca! The rest is history. 7 years later, the famous zebra crossing photo was taken.

Lots of interesting things went on in the studios to make the recordings as good as possible. Floors were covered with big Indian rugs to damp down the reflected sounds. Large wooden screens full of a sort of glass fibre called Cabot´s quilt, were hung from the ceiling and could be positioned to give the right recording ambiance. A lot of time was spent in designing baffles that removed certain frequency ranges to provide a flat recording response.

Echo, reverb chambers had been in use in the U.S since the ´40s to give recordings a “Live” feel as if the recording was made in a concert hall. Abbey Road engineers came up with their own variations. On some recordings, the echo sound was produced by simply putting a loudspeaker at one end of a long corridor and a microphone at the other. A feed taken from the recording studio was fed into the loudspeaker and the slightly delayed signal at the other end of the corridor picked up by the microphone was returned to the recording desk. That signal added back in to the recording gave a “big room” effect. Other more interesting echo chambers consisted of purpose built rooms (EMT140) about 20×12 foot. These had metal and earthenware plates suspended close together. A loudspeaker was fitted at one end and a microphone at the other. The audio from the speaker would bounce around the plates, ending up at the microphone, giving the reverb effect. Other similar rooms were fitted with various lengths and diameter soil pipes, giving a similar but different effect. Tape loop echo machines were also used of course.

By today´s standard, the recording mixing consoles were quite basic. Record Engineering Development Department, REDD31, 37s were common use. These were valve based desks, made by EMI´s German division. There were not too many inputs to play with. 4 at the start but expanding to 12 latterly. Initially everything was mono. Recordings were made on EMI designed tape machines called BTR1, 2 (mono) and 3, which was a stereo, wow! They were huge machines, on wheels, about the size of a washing machine. The ¼ inch tape used was the same as Joe Public would buy. The machines ran at a speed of 7.5, 15 inches a second, sometimes 30 at a push and special occaisions. As time went on, these machines were replaced with Telefunken and Studer machines. An original BTR machine would fetch a lot of money these days. If you have one under the bed, let me know. EMI`s on site development and maintenance engineers were responsible for squeezing every drop of performance from what we would now consider to be a very limited technology!

Microphones such as Nueman, STC and AKG were used. Most of these microphones were condenser types and had valve amplifiers built into their body. The various types of microphones had difference characteristics and were suited to different applications. Drums, orchestral work, piano, rock guitar etc all needed to be treated accordingly.

Processing the audio to be recorded was very important. This ensured that the sound heard when you played the record at home sounded as near to the original recording as possible. EMI designed a tone control box called a “Curve Bender”. This allowed the audio spectrum to be lifted and cut throughout the frequency range from 32Hz to 18,000Hz. The other “must have”, was the compressor. This machine, in basics, allowed the signal to be managed in relation to the dynamic volume range. The recording systems could not deal with the massive change in volume levels that our ears can hear. So a compressor allows the loudest and quietest of passages to be equalized so that when a recording is played back at home, it sounds undistorted and “real”. EMI designed their own compressor, RS114. Fairchild 660 (written about previously) was another industry favoured device. These machines would command a very high price today.

EMI came up with lots of innovative techniques, Single Tape Echo, Artificial double tracking and a noise reduction system way before Dolby, more on which I will write about later. But, this invention, ATOC is really sexy. Automatic Transient Overload Control. This system deals with a common problem faced by the cutting of the groove in vinyl records. The grove in the record is modulated in depth and height in sympathy with the recorded signal. A cutting lathe is used in the master record making process. The spacing of the groove on the record is carefully considered. The closer together the grooves, the longer the recording can be. However, during loud passages, such as lots of bass or drums, the sides of the grooves can be bridged, causing the stylus in the record player to jump about. EMI came up with an ingenious system. The recorded material which was on tape, would, as usual be fed to the recording cutting lathe, making the master record. The cutting lathe set up would have been configured for the type of music being recorded to disc. But, an additional tape machine was included which read the audio a few seconds prior to it going to the cutting lathe. If this signal was deemed to be louder than normally acceptable, it instructed the cutting lathe machine to momentarily increase the spacing of the groves to allow for the extra width of grove modulation. Brilliant. Not only did your record player pick up not jump off the turntable, you had an extra degree of dynamic in the sound. Things like this are so good!